What follows is a spoiler laden discussion of the book Forever War by Joe Haldeman. Beware if you’re worried about such things.

It’s the dawn of a new century and the human race has begun exploring space in earnest after the discovery of ‘collapsars’ which permit instantaneous travel between two distant points in space. Unfortunately, humanity has also discovered it’s not alone in the universe and is now embroiled in a war with a race they call the Taurans. William Mandella has been drafted to serve in this war, and as a result of travel at relativistic speeds, his service will span hundreds of years. Or maybe forever.

It’s the dawn of a new century and the human race has begun exploring space in earnest after the discovery of ‘collapsars’ which permit instantaneous travel between two distant points in space. Unfortunately, humanity has also discovered it’s not alone in the universe and is now embroiled in a war with a race they call the Taurans. William Mandella has been drafted to serve in this war, and as a result of travel at relativistic speeds, his service will span hundreds of years. Or maybe forever.

For the purposes of this discussion, we acquired Forever War as published in book form in 1974, the version which won the Nebula. More recent publications of the novel have been updated by the author to include a different version of the middle episode of the book, which had originally been rewritten at the time of initial publication. Though this new version is better reflective of the author’s original vision, it isn’t actually the version that won. We’ll be discussing our thoughts on the changes in a followup.

J: So we’re up to 1975 and Joe Haldeman’s Forever War. I didn’t know much about it going into it, except that there were some sequels and the series still seems moderately successful. And it was, presumably, a military sf novel. And I actually like quite a bit of military sf, so if I had any feelings about the book going into it, they were probably.. optimistic of an enjoyable experience.

K: That’s a fair description of my feelings going into it as well, though I perhaps knew even less than you did — even though our spreadsheet indicates the sequels, somehow I didn’t even notice it. In any case, I had no reason to be pre-disposed in either direction except that I generally do enjoy military sf as long as the military so described is interesting.

J: What I like about military sf tends to be the military school or the training, the tension in relationships between ranks, the moral and ethical questions of when to disobey orders, and then cool sneaky tricks, like Kirk or Hornblower as just two examples. So when I started this book, it started out interesting for me, because it started out in training. And there were female soldiers!

K: Yes. I was pleased to see them, especially in a book written in the early or mid-70s. I can’t say my like of military sf is quite as quantifiable as yours (and Hornblower isn’t really sf at all — Napoleanic military fiction is pretty large enough to be a genre all on its own), I do like all of those things. And I like ships, water ships or air ships or space ships, it’s all good. But I also like the technology and all of the interesting bits that need to be taken into account to survive and handle restricted environments. And there was a good amount of that here, well-thought out.

J: Oh, no, I wasn’t saying Hornblower was sf. He’s just.. the archetype. In some ways I feel like I want to discuss this book chronologically, as my feelings changed as I read it. But maybe we should mention before we get too far that we read the “original” published version. The version that actually won the Nebula. This book’s publication history is complicated.

K: Right. Now, the book begins right around the turn of the century/millenium. A war is on with an alien race, the only alien race the humans have yet encountered. And for some reason that’s not really adequately explained, the military has specifically drafted a bunch of over-educated college kids to be footsoldiers.

J: The main character was actually born the same year as me. That’s a little trippy. So yea, they’ve recruited these smart college kids, I think the IQ limit was over 140 or something like that? Basically MENSA material college kids, and they’re training them to fight an enemy they know nothing about. Like, hey, we’ve trained you how to kill humans a billion different ways, but none of them may actually work against the aliens. Even the whole idea of having foot soldiers in a fight against aliens is kind of crazy. I’d spend my money on building better ships, but whatever.

K: That did puzzle me quite a bit, actually. The book was very progressive in many ways — spaceflight, the issues with that, the various changes in society and so forth. And yet the -war- was waged — for a thousand years no less — in an manner almost identical to Vietnam. Which was just bizarre, especially since they did not seem to need any of these planets and planetoids they were claiming? It wasn’t clear to me why drones and airstrikes were not being used. Except, of course, it wouldn’t have been the same book.

J: And I couldn’t understand why they thought it was worth the cost of heavy casualties. Heavy casualties /in training/. What a waste of money and resources to have all these people die before ever doing anything useful in the war.

K: Yeah. It all did seem dreadfully inefficient. To send out such a small number of people that even minimal casualties (which were expected!) would totally undermine their ability to actually accomplish the goals of the mission? It’s possible the ludicrous (ludocrisy?) was intentional, since he was probably trying to draw parallels with Vietnam. To the point where most of the training officers are gung-ho Vietnam vets.

J: I wouldn’t have thought Vietnam at all, except that he did mention it in his intro, which I read afterwards. You know I did wonder why he thought there hadn’t been any wars after Vietnam until the 90s! Um.. apparently anywhere on the planet. This isn’t an American-only strike force, is it? Certainly he made some attempt with the names to be multi-cultural.

K: No, it’s not an American only strike-force. The history is a bit sketchy to me, but this is what I worked out. Some assumptions may be incorrect. History is normal up until the ‘present day’ ie, when the book was written. After that though, the space program appears to remain better funded than it did. No fuel crisis? In 1985, collapsars, jump points, wormholes, whatever, are discovered, which presumably injects more excitement and urgency and funding into the space program. At some point, Earth’s space programs are taken over or overseen by the United Nations, who creates UNIT UNEF. By 1997, they’ve had very brief alien contact and declared war on the other species. The “Exploratory Force” is converted to a military one and people start getting drafted. That’s the beginning of the story.

K: Histories of the future are always a bit dubious, though this one seems especially so given the rabid xenophobia that dominates the U.S. political landscape today. I can’t imagine the reaction to the United Nations trying to take over anything.

J: The United Nations turning into a world government of some sort is fairly common in sf, at least historically. So that part makes me just roll my eyes and say ‘Whatever’ and move on. Rather like all the pot-smoking in this book. Whatever. And, at some point, I start having to say ‘Whatever’ to all the rampant orgies in 60s and 70s sf. Like, really, this is the future of the human race? Drugs and orgies?

K: But doesn’t that sound like fun? Doesn’t it?! The drugs thing is still a very common trope today. And not entirely far-fetched, I must say. But even as a social super liberal, I cannot see the orgy thing taking hold, at least not in the near term future.

J: Let me mention the line that really ticked me off, just to get it over with. I was reading the book at lunch and just had to stop. And wish I’d brought a second book to lunch with me. Here’s the quote:

The orgy that night was amusing, but it was like trying to sleep in the middle of a raucous beach party. The only area big enough to sleep all of us was the dining hall; they draped a few bedsheets here and there for privacy, then unleashed Stargate’s eighteen sex-starved men on our women, compliant and promiscuous by military custom (and law), but desiring nothing so much as sleep on solid ground.

J: There’s just so many things wrong with that. I just got so mad, because up until that point he’d been treating the male and female soldiers pretty much equally. They had this sex rotation where they’d sleep around, which I didn’t object to too much. Only to wonder why they were all apparently straight and none of them had the desire to be celibate. No partners back home? No religious feeling? No.. just.. low sex drive? Out of, what was it, 100 people? But then this line hit and it was like he’d undone everything he’d set up before it in turns of gender equality.

K: When you mentioned there was a line that made you want to smack him, and I came to that line, I knew it was the one you meant. Because it jarred me in the exact same fashion. He included women. They appeared to be equal to men. There was no griping about women being weak or not allowed in combat or any other nonsense of that nature. And then, suddenly — what?! It made me question everything. Did they include women in these roles out of a realization that women were equal and should be treated as such? Or did they just find a convenient way to include sex workers and oh hey, we can also get extra work out of them! Except it was even worse than the latter, because apparently the women are not only sex workers, they apparently have no legal right to say no, even if they don’t want to. I’m surprised no one in the present day has hit upon this way to solve the issue of military rape. Just declare it legal! Problem solved!

J: I don’t like to say anything about the book while we’re both reading it, but I just had to at least say something! And jeez, don’t let the GOP get hold of this book. ‘Hey, we have this great proposition for you. I know you’re studying to be a nuclear physicist, or whatever, but we’re going to make you join the military. You might die in training, you’ll almost certainly die before your term is up, and oh yea, you have to have sex whenever the male soldiers want. And they’re randy devils who’ll want it ALL THE TIME. Because that’s how college-age guys are. But it’s okay, because they’ve all had vasectomies. Sounds good, right? Now go shoot some aliens!’

K: It did make me wonder, considering it’s also established at the same time that the government has technology that allows them to modify your behavior and the way you think. Did they modify the women to make them okay with this? And if so, why not just modify all the soldiers and make them asexual for the duration? It seems like that would have been better for ‘unit cohesion’ if you get down to it.

J: Yea, you don’t want your soldiers wasting time and energy on something essentially useless, do you? Especially as they’re apparently very closely monitoring their caloric intake and exercise. Less energy spent on sex = less food you need to ship up into space with them. Actually I think they did say they gave the officers, who were required to be celibate, hypnosis or whatever to make that easier. So might as well do that for everyone.

K: Except the officers were boffing people too, so I’m not sure why that particular hypnosis didn’t work even though everything else did.

K: Anyway. Aside from that jarring bit, which lent absolutely nothing to the plot and could easily have been removed without anyone noticing, the book resumed course and we started to get into the ‘forever’ part of the Forever War.

J: Yup. Basically they go fight, then they come back to a base of one sort of another, years have passed, the world has changed. I think the time jumps get greater as we go along, but that’s because the main character is going on further-out missions. And with this time effect, when they encounter the aliens they’re fighting, the aliens might’ve had decades to advance in tech, while they didn’t. And then vice versa. So it’s usually a rout in one direction or the other. Which seems a really bad way to fight a war, but y’know, space, what can you do.

K: It does seem like an increasingly silly situation, especially from the perspective of the soldiers, which I’m sure again is some sort of Vietnam parallel exaggerated hugely – the completely out of touch commanders, planning things far away in space AND time. And, it seems, with the people at home completely removed from the war aside from occasionally being drafted. Because it has no bearing on them one way or another; they don’t seem to be in danger of being invaded, ever. It’s an abstract concept to them, especially given what must be years and months between every individual engagement.

J: Which leads me to a question I had at the end, which was how did they know it was the last ship that needed to come back? Given that earlier it said a bunch were ‘missing’ and possibly taking essentially the long road home. Because these guys aren’t operating with an ansible. Which Le Guin had already invented, so they could’ve been!

K: All right, we can skip to the end, though I thought we were going to go through this chronologically! Anyhow, I was a bit mystified by this declaration as well. It didn’t seem like there was any reason to know for sure that they were ‘last’, unless everyone else had been confirmed dead or returned (and we’re not given that information.) Also, it’s mentioned when they come in that there are lots of ships all around this base. Then it seems like the base is mostly abandoned and will be destroyed when they leave — it was just being maintained until they got back. So what are all those other ships? I was confused.

J: Yea, that confused me too! And if you knew they were last, and you knew their route, why not go and meet them? And presumably be able to fly them back faster or at least more comfortably, with your advanced technology. But yea, we should probably go back, to the first time the main character comes ‘home’ and sees what the future has wrought.

K: Right. But this first visit is after only a few years — 25 or 26 — so he’s still at a period of time when he’d be alive, and his relatives are alive, though greatly aged. We get a little bit of information about recent events and the current political situation on the planet. It’s sort of a dystopian situation, except that we experience it so very briefly that it’s hard to have much of a reaction to it beyond ‘ugh’.

J: Except my reaction wasn’t even ‘ugh’. Most people are unemployed, but the government makes sure they have enough to live on. And they’re free to pursue whatever interests them. I could see how it could lead to depression. If you’re not doing meaningful work, then it’s not good for your well-being or the society’s well-being. But it depends on what they’re allowed to do. It seems like no matter how well-run your economy is, you can always use more art of all kinds. Or people out there tinkering with this and that, inventing things. So I failed to see what was so horrible about not having a job. And of 1/3 of your neighbors being gay.

K: Yeah. That part seemed more or less okay, though it’s unclear how it’s being paid for — and then we basically find out that it’s being paid for by sharply rationing healthcare to the point where many people are not allowed to have any. They’re provided food and shelter, but not much more. This whole section seemed very abbreviated to me, like things were being thrown at us and we were clearly supposed to find them bad, but I’m not sure there was enough information to make that determination in all cases.

K: Even the healthcare thing was weird, because you know as soon as the government limits something like that, a black market appears to fill the vacancy. So where were the back alley doctors? We don’t get a sense of any of that. Everyone’s completely isolated from one another, apparently.

J: I thought everyone got healthcare until they turned 70 and then some people didn’t merit it. It seemed a little extreme in that they didn’t give them any care, when it wouldn’t really cost much to give out a few pills for an acute ailment. And you’re absolutely right. Where are all the unemployed people with enough education to be doctors? Certainly the two main characters at this point don’t seem to give the place much of a chance before they run back to the military and sign up again.

K: Yeah. I’m sure there was some underground rebels or… something. But they spend a week there, throw up their hands and leave again in disgust. Was it really worse than almost certain death in the military?

J: The wild amount of money they’d earned from their decades of service amused me. By how pitiful it actually looked. :)

K: Yeah, it was pretty sad, though after a few hundred years it was a lot better.

K: Which brings me to another bit, as we’re sort of up to the interlude where they ended up on ‘Heaven’, a hospital and recreation planet. Which is, these humans never did invent the ansible, so they have no instantaneous communication. In fact, communication between Earth and distant humans seems practically nil. So what is keeping them in line? Heaven seems like a pretty nice place, so what has prevented them from just declaring independence and going on their merry way as an entity separate from Earth’s political system?

J: Oh, didn’t they say the entire economy was based on rich soldiers spending all their wealth? That didn’t seem like it’d work, somehow. Maybe communications is part of it. Are they really going to get all that money from Earth when they turn in their bills, or whatever? And just how long will it take?

K: It does seem like there’d need to be incredible redundency in bank and personnel and health care records to sustain a multiplanetary nation without the ability to communicate at a reasonable rate of speed.

J: I don’t really remember much about what Heaven was like, except they toured around and climbed mountains or something. And I also forget what came right after that.

K: At the end of it, William and Marygay were assigned to different companies and sent off to different missions. He headed back somewhere. Stargate? and got reoriented in time, because by the time he got there it was about 100+ years later. Then he got his assignment out to the back of beyond.

J: Ah okay. That’s when he got all the brain training in how to fight with all sorts of random weapons and learned tactics and strategy. And then they give him a squad or whatever it was of his own. Full of fresh-faced young kids about 5 years younger than him.

K: Right. And all homosexual.

J: Which was neat, in a way. When gay people started showing up, it sort of went some way to making amends for that egregious line from early on. (Not that including gay people makes it okay to be horrible to the entire female population of your book, but that you could maybe feel he was trying to show a contrast in gender and sexual relations across time periods and had maybe exaggerated the first bit for effect.) The main char’s troops call him Old Queer and see him that way, and that was an interesting take on it. But by the time I finished the book and could look at the role of homosexuality in the book as a whole.. it didn’t work well. It only shows up and is only encouraged to keep down the population. Which is a really stupid reason.

K: Exactly. I do think, for the time, it was probably a pretty progressive book. There were women, the women were fellow soldiers, not nurses. They were competent. There were gay people — in the military! — and homosexuality was shown as an accepted norm. On the other hand, the idea of turning people homosexual for population control is a bit strange. Just because you’re homosexual doesn’t mean you lose your desire to reproduce. Just the ability to do so naturally while still having sex with your preferred gender. Again, here’s a situation where asexuality would work far better if you’re looking to divert people from any sort of sexual reproduction.

J: There was even a female doctor. But yea, asexuality comes to mind. Or any number of methods of birth control. Free vasectomies for all! Or just start breeding for infertility. And this is a major spoiler, oh no, but the only gay character we care anything about at the end of the book… is turned straight. So he can marry and presumably have babies and live happily ever after.

K: Heh. Yeah. I wasn’t too sure about the tone exactly — I mean, why not just be a gay guy on this new planet? What was the harm in that? I do think human sexuality is more of a spectrum than a binary, but exploring that idea was definitely not part of this book’s goal, nor was it really presented that way.

J: I would be interested to know if and how it’s explored more in the sequels. But interested enough to actually read them, I don’t know.

K: I’m not sure either. So what was your opinion of the book overall, now that you’ve actually read it?

J: Well, I dunno. I definitely saw it as a forerunner of some of the ideas in Ender’s Game and the Shadow books. And parts of it reminded me of Old Man’s War. So it was interesting. I just don’t think I really liked it as a cohesive whole of a book.

K: Ha. You should definitely read the intro Scalzi wrote then, before we return the books. And yes, I can see how other books picked up on the ideas here — Ender definitely seems almost like this book from a different perspective, though they clearly have instantaneous communication as well. I ended up enjoying it a lot more than I expected after that gang-bang scene, and had that not been included, I would feel pretty good about the book as a whole. But it makes me very uncomfortable to approve of it.

J: Ender’s Game has an ansible. OSC was stealing more than we realized when we first read it. :) Also the part where some of the militarily-trained people come back to Earth and try to start a revolution. Because they are heroes, and they are trained. (Which I find a little confusing because I thought it was like a 99.somethingcrazy% death rate.) But yes, I certainly can’t heartily endorse the book by any means. There’s also another line that really ticked me off. The main char encounters someone he can’t tell the gender of. He mentally flips a coin and ‘comes up tails’ and decides she’s a woman. I don’t know if that was an intentional play on words, but I was not inclined to be generous with him at that point.

J: Though if that had appeared in any other book, I would’ve brushed it off and forgotten it. It was only because he’d done such a good job mostly of including women equally.

K: I don’t really remember that scene, so I guess it didn’t have much of an impact on me.

J: One other thing, because I think we’re about done and I wanted to mention it. The first encounter with the aliens, there are these animals that like.. brain-kill everyone with a high ESP rating. And then.. the ESP thing is never, ever mentioned again.

K: Yes! I had totally forgotten about it, but yes. It was really a strange encounter. You’d think over the 1000 years, they’d attempt to develop this ESP more, especially once they start straight out breeding people rather than relying on random chance for reproduction.

J: I suppose that clone being thing, they’re all connected telepathically, or.. by something. It’s not clear. I don’t know if the ESP was dropped because this novel started life as a series of stories or just because sometimes you throw in some psi powers just because.. they’re pretty ubiquitous in sf at this point in time.

K: Should we mention the ending? I will say that it was painfully obvious to me that the war was going to turn out the way it did, but I was still sad to be proven correct. Was the ending considered shocking back in the day?

J: No idea. I was actually thinking at one point that maybe it would turn out they were fighting some form of humanity from the future. Alas, not that interesting. Though after I thought it, I would’ve been disappointed to have been proven correct.

K: Any last thoughts? There appears to have been an absolutely enormous nominated field for the Nebula in 1975. Have you read any of the others? Did it deserve to win?

J: Dhalgren and The Female Man get mentioned a lot in feminist circles, but I don’t believe I’ve read either. I have not read Heritage of Hastur, I don’t think, though I do mean to read more MZB. I may have read The Mote in God’s Eye in high school. All of the others, I haven’t heard of. So why Forever War? I was wondering if it wasn’t a reaction to the relative passivity and pacificity of The Dispossed. They needed a good war story with lots of gory dead bodies. Or it could just be that a lot of the votes got split, I dunno.

K: I’m not sure. Probably at the time, the war motif, especially the parallels to Vietnam, were far more at the forefront of everyone’s mind. I can’t say that I’ve read any of the other nominees, though I have heard of several. Based on the influence it obviously had on later books, I’m not going to say its win was undeserved. And it was a very readable book.

J: And Niven and Delany at least had already won before. I’m sure some voters considered that as a factor. Ha. It just occurred to me we do have to read at least one sequel, because Forever Peace occurs later on the list.

K: From what I can tell, Forever Peace is not a sequel. It didn’t look like it even takes place in the same universe.

J: Er… okay. *puzzled*

For 2012, the three of us at Triple Take have decided to focus on YA fiction from Australia and New Zealand. First up is the first volume (January) of Gabrielle Lord’s Conspiracy 365 series, in which a teenage boy named Cal must survive attacks on his life for the next 365 days whilst investigating his father’s mysterious death. The publishing schedule was pretty nifty for this series, with the first twelve books (named after the months of the year) coming out throughout 2010 during the month reflected in their title. The thirteenth book in the series, Revenge, was published in Australia in October 2011, but hasn’t made it to the US yet.

For 2012, the three of us at Triple Take have decided to focus on YA fiction from Australia and New Zealand. First up is the first volume (January) of Gabrielle Lord’s Conspiracy 365 series, in which a teenage boy named Cal must survive attacks on his life for the next 365 days whilst investigating his father’s mysterious death. The publishing schedule was pretty nifty for this series, with the first twelve books (named after the months of the year) coming out throughout 2010 during the month reflected in their title. The thirteenth book in the series, Revenge, was published in Australia in October 2011, but hasn’t made it to the US yet.

It’s the dawn of a new century and the human race has begun exploring space in earnest after the discovery of ‘collapsars’ which permit instantaneous travel between two distant points in space. Unfortunately, humanity has also discovered it’s not alone in the universe and is now embroiled in a war with a race they call the Taurans. William Mandella has been drafted to serve in this war, and as a result of travel at relativistic speeds, his service will span hundreds of years. Or maybe forever.

It’s the dawn of a new century and the human race has begun exploring space in earnest after the discovery of ‘collapsars’ which permit instantaneous travel between two distant points in space. Unfortunately, humanity has also discovered it’s not alone in the universe and is now embroiled in a war with a race they call the Taurans. William Mandella has been drafted to serve in this war, and as a result of travel at relativistic speeds, his service will span hundreds of years. Or maybe forever.

The Plot

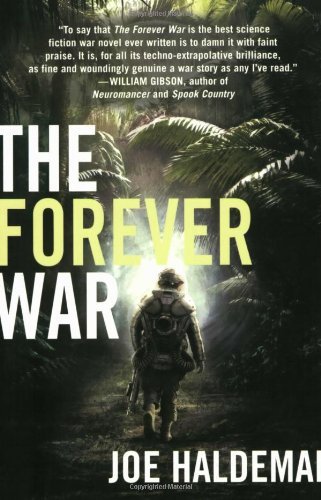

The Plot Finally, I would be remiss if I didn’t comment on the truly appalling cover art on the edition of the book which I read. It is hideous. If I had picked this book up off the shelf in the bookstore, intrigued by the title, I would most likely have put it right back down after seeing this bizarro picture on the front. Fortunately, more recent editions have come out with a much more modern, appealing set of covers.

Finally, I would be remiss if I didn’t comment on the truly appalling cover art on the edition of the book which I read. It is hideous. If I had picked this book up off the shelf in the bookstore, intrigued by the title, I would most likely have put it right back down after seeing this bizarro picture on the front. Fortunately, more recent editions have come out with a much more modern, appealing set of covers.

With the exception of Farmer Boy, the original Little House books all have Laura Ingalls as the main character. Though the books themselves follow her as a child all the way to the first years of her marriage, there’s a time jump* between the third Laura book, On the Banks of Plum Creek and the fourth, By the Shores of Silver Lake. The existence of this gap means it makes sense to me to break the series there and have a look at the first three books together.

With the exception of Farmer Boy, the original Little House books all have Laura Ingalls as the main character. Though the books themselves follow her as a child all the way to the first years of her marriage, there’s a time jump* between the third Laura book, On the Banks of Plum Creek and the fourth, By the Shores of Silver Lake. The existence of this gap means it makes sense to me to break the series there and have a look at the first three books together.