The Plot

The Plot

It’s the summer holidays, Christmas is over, and Ellie and her friends are looking to have some fun before school starts again. A mixed group of boys and girls set out on a camping trip into the bush and are gone for several days. When they return home, things are not right: homes have been ransacked, parents are missing, and pets and other animals are dead. They soon discover, to their horror, that the country has been invaded and most of the town captured.

My Thoughts

I’ll begin by stating that I’ve never been a huge fan of the dystopian genre. It’s hard for me to explain exactly why: I’ve read many examples of this genre and even enjoyed them. They’re often very important books, which can serve to illustrate the slippery slope society is currently on, or could easily begin rolling down. But on a fundamental level they bother me. It’s not just that the excuse for the dystopian elements being introduced is often flimsy or poorly explained (but that is a big and common problem). It may be that I just don’t really want to think about the world being so disturbingly screwed up. Especially since much of the time these books don’t really provide any hint that conditions will improve for most people even after the heroes have done what they’re going to do.

That said, while Tomorrow, when the War Began shares many traits with books in the currently burgeoning Dystopian YA category, I’m not sure if I would put it there or not. My feeling is that in a typical example of the genre, you begin with the dystopic situation already well-established. Whatever events led to its creation may or may not be within living memory or even remembered at all. In either case it’s usually very entrenched by the time the reader and the hero arrives on the scene. That is not the case here. Ellie and her friends are typical rural Australian teens, living in or near a small town with their families. Their lives are normal (though pre-internet and cellphone, as this was originally written in the early 90s). They decide to have a camping trip into the bush to better enjoy the tail end of summer vacation before school starts up again, so a group of seven boys and girls head off to camp in an area even more remote than some of their family ranches. Author Marsden takes advantage of the camping interlude, which comprises the initial 20% of the book, to try and flesh out the characters as they are before circumstances will force them to change. His success there is only middling, as it’s difficult to establish the personalities of seven individuals in such a small space without resorting to stereotypes to fill in the blanks. Happily, he mostly avoids using such stereotypes as a crutch for most of them, with the exception perhaps of Fiona, who seems to me pretty much straight out of the rich-pretty-girl box.

The action gets started when our group of high schoolers returns from their camping trip to find something strange has happened. The family ranches which they arrive at first are abandoned, animals have been killed, the power is out, and there’s no hint as to where the people have gone. We have another instance of win here where the kids are appropriately creeped out and cautious as a result of these oddities, but not really ready to let themselves imagine what might have happened. (Though I did find it odd that none of them seemed to speculate about alien abduction. Is that just too ridiculous? But the situation was bizarre! If that’s not a time to let your imagination out, I don’t know when it is.) They soon conclude the area has been invaded by some outside aggressor, a conclusion which is confirmed when they find a fax sent by a parent waiting for them at one of the abandoned houses.

What I most enjoyed about the book at this point was that the ambitions of the characters matched their abilities and knowledge. They did not (spoilers!) put together an amazing plan to destroy the invaders; they did not hack into the national defense system and save the world; they did not even come up with an improbable and complicated plan to free all of the hostages being held at the camp in the town. They kept their goals small and attainable, and had a realistic amount of problems in executing them. They were upset, scared and tempted to try and run away from it all — and not at all positive that wouldn’t be the best course of action anyway.

That’s not to say it was perfect. Perhaps its biggest weakness was the treatment of the female versus the male characters. While everyone is portrayed as very competent and there’s no real arguing that the girls are going to be equal and equally effective partners in their resistance efforts, was it really necessary to have the only two characters to have a dramatic mental breakdown be female? I don’t think it would have affected the story at all if, say, Kevin had been the one to see his home destroyed and had gone hysterical as a result. That it was Corrie instead just undercut the generally positive portrayal of girls in the book.

Finally, I would be remiss if I didn’t comment on the truly appalling cover art on the edition of the book which I read. It is hideous. If I had picked this book up off the shelf in the bookstore, intrigued by the title, I would most likely have put it right back down after seeing this bizarro picture on the front. Fortunately, more recent editions have come out with a much more modern, appealing set of covers.

Finally, I would be remiss if I didn’t comment on the truly appalling cover art on the edition of the book which I read. It is hideous. If I had picked this book up off the shelf in the bookstore, intrigued by the title, I would most likely have put it right back down after seeing this bizarro picture on the front. Fortunately, more recent editions have come out with a much more modern, appealing set of covers.

In Short

Tomorrow, when the War Began is a solid entry in the genre of YA speculative fiction with a dystopian bent. It also scores well on gender equality, though there were a few bits here and there along those lines that troubled me. It would work well enough as a standalone book, but it very clearly leaves so many threads unresolved that it’s a good thing the series continued. Even though the topic isn’t exactly my cup of tea, I may find myself tracking down the rest to find out how it all turns out.

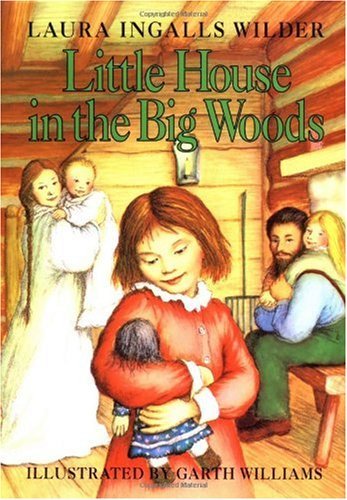

With the exception of Farmer Boy, the original Little House books all have Laura Ingalls as the main character. Though the books themselves follow her as a child all the way to the first years of her marriage, there’s a time jump* between the third Laura book, On the Banks of Plum Creek and the fourth, By the Shores of Silver Lake. The existence of this gap means it makes sense to me to break the series there and have a look at the first three books together.

With the exception of Farmer Boy, the original Little House books all have Laura Ingalls as the main character. Though the books themselves follow her as a child all the way to the first years of her marriage, there’s a time jump* between the third Laura book, On the Banks of Plum Creek and the fourth, By the Shores of Silver Lake. The existence of this gap means it makes sense to me to break the series there and have a look at the first three books together.