With the exception of Farmer Boy, the original Little House books all have Laura Ingalls as the main character. Though the books themselves follow her as a child all the way to the first years of her marriage, there’s a time jump* between the third Laura book, On the Banks of Plum Creek and the fourth, By the Shores of Silver Lake. The existence of this gap means it makes sense to me to break the series there and have a look at the first three books together.

With the exception of Farmer Boy, the original Little House books all have Laura Ingalls as the main character. Though the books themselves follow her as a child all the way to the first years of her marriage, there’s a time jump* between the third Laura book, On the Banks of Plum Creek and the fourth, By the Shores of Silver Lake. The existence of this gap means it makes sense to me to break the series there and have a look at the first three books together.

The Plot

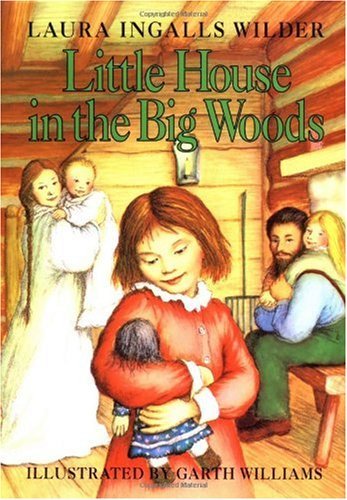

In Little House in the Big Woods we’re introduced to the Ingalls family – Ma, Pa and their daughters Mary, Laura and Carrie. They live in a tiny cabin in the midst of a forest that’s pretty much on the border between Wisconsin and Minnesota. The family isn’t wealthy, but they’re able to live well enough off the land – both theirs and the unclaimed areas of the forest. But soon enough, Pa is beginning to feel the forest is oversettled, and the whole family moves to Indian Territory in Little House on the Prairie. Pa believes the Native American tribes will soon be forced to give up this land (as do quite a number of others) and he and the family set up a farm just inside the disputed border. When he hears a rumor that soldiers will be coming to displace the settlers, he angrily packs the family up and they depart for Minnesota, where they settle during On the Banks of Plum Creek. Relatively close to a town for the first time, Laura and Mary are finally able to attend school, while Pa once again takes a stab at building a farm.

My Thoughts

These first three Laura books cover the period when she was about age 4 until 9 or 10, and follow the Ingalls family as they live at three different locations. We begin in Wisconsin, where the family is living in a small cabin in a forested area near the town of Pepin. The cabin is tiny, and life surely wasn’t quite as rosy as the picture Wilder paints, but even if the depiction of her childhood is romanticized, it’s still engrossing in a way that’s hard to explain.

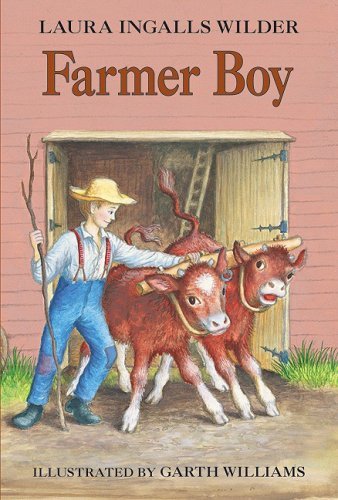

We’re introduced here to the family: Pa, Ma, older sister Mary, Laura, and baby Carrie. Pa is a bit of a jack of all trades – he farms just enough to provide food for the winter, but obviously much prefers the variety of hunting and trapping with occasional other projects to the steady monotony of farming. Ma supervises the children and the food as well as performing numerous other important tasks around the homestead. Mary and Laura assist Ma with her work and Pa as needed; as with the Wilders in Farmer Boy, gender roles are enforced to a point, but if work needs to be done, then whoever can do it will be required to help out.

Compared to the industrious Wilders in Farmer Boy, the Ingalls family is positively idle. Which is not to say they aren’t constantly working, but without a large farm to take care of, the daily tasks of taking care of the stock and the garden are much less labor intensive. Pa spends a great deal of time tramping through the woods — hunting and trapping and fishing to be sure, but also enjoying himself while doing it. Ma certainly knits and sews, but it’s not clear that she has the materials for the sort of spinning and weaving that Mrs. Wilder was able to do. Interestingly, Ma, a former schoolteacher, does not really seem to press academic lessons very hard on Mary or Laura; both girls seem to have lots of free time in which to play.

But it’s not so much the plot or even the characters which make these books so fascinating. As I mentioned in my comments on Farmer Boy, it’s the details that drive my interest. Wilder was aware she was writing about a way of living already foreign to most of her readers, who had grown up with automobiles and the A&P. She took the time to describe the process of how things worked — from the perspective of a child — and include interesting details that just captured the imagination. If someone confronted me with a roasted pig tail I would probably recoil, but reading about Laura and Mary’s delight in the treat makes me want one: it sounds absolutely delicious.

The drawback to the weight given to process detail, and the fairly episodic nature of these early books means that the characters themselves are not deeply drawn. Ma is quiet and efficient, Mary is good and ladylike, Pa is mischievous and a good provider, Carrie is a baby, and Laura is restless and naughty. Part of this is, I think, because the Ingalls children themselves are so young in these books, it would be difficult to draw a more nuanced portrait of Ma and Pa while still retaining Laura’s perspective. And part of this is because they are meant to be idealized versions of the Ingalls family. Living in a tiny shack in the woods of Wisconsin cannot have been an easy life, no matter how rosy a picture Wilder tries to paint, but to start with real hardships are pretty much glossed over: everyone is well-fed, warm, and comfortable, even if they don’t have lots of possessions.

By the time we reach Plum Creek, the girls are starting to grow older and are more aware of their own lack of wealth relative to others around them. Nellie Olson appears on the scene for the first time, providing a sharp contrast to the Ingalls household with her heaps of toys and dresses, furniture and books. Something I didn’t pick up on reading as a child, but which comes through clearly now, is Charles Ingalls’s restless and somewhat irresponsible nature. His move to Kansas may have been well-considered, but to leave in what amounted to a fit of pique was truly shocking, and his decision for the family to settle near Plum Creek was poorly researched to say the least. Surely the fact that the man he bought the land from was so eager to get out of Dodge should have given him a clue? (Hint: When the oldtimers are talking about “grasshopper weather”, ask them what they mean!) And then he falls victim to easy credit, building a house without any actual money to pay for it. I’m left with the feeling that if he were alive today, his mortgage would be underwater and he’d be up to his eyeballs in credit card debt in spite of his ideals of self-reliance.

And I can’t much speak for Caroline Ingalls either. Though she is obviously part of the decision which brings the family to Plum Creek, because of the proximity to a school for the girls, she seems in no hurry to actually send them — she keeps them home most of the first year they live there, for no good reason. As a child, I never noticed it, but it does seem odd to me that the very clever daughter of this ex-schoolteacher heads to school around age eight just barely knowing her alphabet. Especially when Mary can apparently read? I am not sure what was going on there.

But none of these were things I noticed when I read them long ago, and even seeing them now and knowing more about the real Ingalls family and how they differ from the book version doesn’t take away from the charm of these books. It’s easy to see why they’ve inspired such a fandom as they have.

*Recently, the author Cynthia Rylant has attempted to bridge the gap by writing a midquel, Old Town in the Green Groves to cover this missing period, a book I’ve not yet decided upon reading.

In Short

The first three Laura-focused books in the Little House series covers a span of five or six years in Laura’s life, during which her family moved several times to radically different locales. Wilder describes their lives in each location, dwelling on interesting incidents and pulling these anecdotes together into an idealized portrait of her early life. Though reading them as an adult allows one to pick up on undercurrents that a child probably wouldn’t notice, nothing detracts from their charm and interest. These are books I will and have read again and again.

The Plot

The Plot

The Plot

The Plot