The Nebula Project returns from hiatus with a guest panelist (K’s husband Bob, able to, among other things, provide a male perspective) and a discussion of Arthur C. Clarke’s Rendezvous with Rama.

In the 22nd century, humans have spread out all over the Solar System, colonizing everywhere from Mercury to the moons of the gas giants. But in spite of their expansion, the fabled ‘space drive’ has still eluded scientists and many believe it’s not even possible to construct. All is thrown into question by the appearance of a strange object which enters the Solar System on a course to swing around the sun. The object is clearly artificial — the work of another race. The spaceship Endeavour is the only ship within range of its projected path and thus its crew is given the task of making contact with the object, now named “Rama”, and attempting to collect as much information as possible before its path goes too close to the sun for humans to follow. Though the collective governments of the various human settlements are excited by this unprecedented arrival, they are also quite nervous: is Rama a threat? The Endeavour crew will need to try and discover that as well.

In the 22nd century, humans have spread out all over the Solar System, colonizing everywhere from Mercury to the moons of the gas giants. But in spite of their expansion, the fabled ‘space drive’ has still eluded scientists and many believe it’s not even possible to construct. All is thrown into question by the appearance of a strange object which enters the Solar System on a course to swing around the sun. The object is clearly artificial — the work of another race. The spaceship Endeavour is the only ship within range of its projected path and thus its crew is given the task of making contact with the object, now named “Rama”, and attempting to collect as much information as possible before its path goes too close to the sun for humans to follow. Though the collective governments of the various human settlements are excited by this unprecedented arrival, they are also quite nervous: is Rama a threat? The Endeavour crew will need to try and discover that as well.

J: I’d read some Arthur C. Clarke when I was a teenager. I thought Rendezvous with Rama would be easy to read and interesting. But.. not so much. My overall impression after having read it is that it would’ve made a far more interesting short story.

B: I could certainly see this being adapted to a short story form, although it would mean cutting some things out. And you could probably cut out things like the lengthy explanations of the politics of the situation, or some of the background technologies that could have just been left for granted. But I actually kind of appreciate having them there, even it means the story progresses at a glacial pace.

K: It definitely does progress at a glacial pace. But I actually did like that: I agree with J that the story could easily have been shortened, but it would have ended up a much different story in that case. It was clear that Clarke had given a lot of thought to what technologies might be found in this environment and why and he wanted to get across very clearly the issues that humans were going to encounter when attempting to understand a completely alien species with nothing but a single (very large) artifact from which to draw conclusions. So I felt like the pace was justified, and I didn’t find it too boring. Slow, but not boring. Though I also had a hard time shaking a feeling of forboding; it really really read in parts like a horror novel, and I couldn’t help but keep waiting for something inexplicably awful to happen.

J: If the characters had been.. actual characters, I wouldn’t have minded so much. I guess I’m just not into the ‘explore this strange thing’ as the main driving point of a novel.

B: The characters were fairly generic, I will give you that. They did not go far beyond the archetypes they were modeled after, other than little personal touches like the captain’s multiple families, that engineer guy’s religious background, and so forth. But expanding on K’s point, not only did Clarke go to great lengths to write about the challenges of exploring an alien environment, he also spent a lot of time on the background challenges as well — getting the approval of governments, getting funding, maintaining public support… I cannot think of many examples of stories that go that far into the depth of the situation. It comes at the expense of interesting characters, certainly, but if you can get past that, there is a lot there that is still interesting.

K: Yes, the characters were absolutely generic. Even though there were some passing efforts made at establishing a backstory for them, they didn’t add much, if anything, to the story. Things were just stated about them – such as the random existence of plural marriage – without explanation or context. I didn’t exactly want an infodump on the socioeconomic status of the Solar System, but if you’re going to bring up interesting social points, you shouldn’t just lob them out there and let them thunk on the ground without further attention. It was distracting. I spent a good amount of time trying to figure out things about the various planetary/colonial societies when that was neither the focus nor the purpose of the book.

J: I was definitely hoping to see these wives of the captain. Why they married him, since he’s such a jerk about it, writing them generic letters. And that, yea, I think it’s _one_ mention of these other two guys who are together and have a wife/girlfriend back home. Instead the guy who seems to get the most attention and screentime is the guy who flies around.

B: Well, Jimmy (of course his name was Jimmy) was just about the only character who saw any actual action. Everyone else mostly climbed up and down stairs, looked through telescopes, or cut into things. (Alright, I’m oversimplifying a little — there was a lot of background activity — but almost none of it was anything I would call action.) Also, until the very end, he is the only one who actually discovered anything concrete about Rama. It was his trip that really provided the most clues, by a large margin, about what Rama was actually doing out in space.Getting back to the sociopolitical info-dump for a second though, I think that was Arthur C. Clarke, Futurist, seeping through into the story. I read a bunch of other essays of his with much of the same kind of thing — in the future, there will be fewer social restrictions, buildings will be way sturdier, people will stop wearing clothing, etc. As far as what goes on in the story, though, you can pretty much ignore all of it.

K: That is interesting. I’ve not really read a great deal of his writing, so I just had this to go on, and I found it very difficult to pin down his views from here. (On social issues, that is.) On the one hand, societies which allow a man to have more than one wife are typically regressive and patriarchal. But here we also have the suggestion that women can have more than one husband — though he then sort of negates that by suggesting the guys may have come up with the idea and that they’re also bi. (Progressive in and of itself, but it doesn’t speak toward the status of women.) So there was progressiveness, but it wasn’t pervasive in all aspects of life. Judging just from this book alone, I can’t say I’m impressed with his future thoughts on the place of women in society. Yes, they are there on the ship – there’s even more than one – but their authority is either low or outside the general command structure. And there appears to be only one female scientist on the big Alien Encounter Council they convene (though for a few minutes I thought there would be zero, so at least we avoided that scenario.)

J: Yup. And his wives are both at (separate) homes taking care of the kids. Just a very typical arrangement, especially for a ship captain. He just happens to have two of them. Along with women, the society or societies if you want to call all the other planets/colonies that seemed also very white American/European. Despite calling it Rama, which we can discuss by itself, I only saw like one or two character names that could’ve been Indian or Asian. Even though it would’ve been dead simple to throw in names from all over. And for character descriptions, I don’t think he ever bothered to specify what race people were. At least for the most part.. my memory may be iffy here.

B: This book certainly does not come off as a shining example of progressive thinking, but it’s definitely farther than it could have been. If it were rewritten now, the captain would probably have been a woman with multiple husbands, and there would have been a greater diversity of ethnicities, genders and ages. Then again, he leaves so much to the imagination as far as the characters go, they really could have been any ethnicity, if not for their names. (Come to think of it, Jimmy’s last name, according to my five minutes of internet research to refresh my memory, is “Pak” — so his ethnicity could be debatable.) On the other hand, we are talking about a book from almost 40 years ago, so the progressive movement wasn’t as far along as it is now, so I’ll give him at least some credit there.

K: I definitely read Jimmy as of Asian ancestry of some sort. Perhaps because of the last name, or maybe it was even stated, I’m not sure. In any case, I think it’s true that most of the characters have so little information provided that there’s no reason they had to be white, though one might get the impression Clarke imagined them to be so. But I don’t think there’s any real proof either way. He was definitely far more interested in the thought experiment of the aliens.

J: Clarke had been living in Sri Lanka for more than 10 years by that point. Which makes me think he could’ve done a better job of making things appear global. From what little I know/remember of his other work, he is big on aliens. And on aliens that are more advanced than us. And the way those machines were eating things, it’s very easy to visualize this as an anime.

B: I definitely agree there: this is a story about humanity exploring an alien landscape. The actual representatives of humanity in the story are generic and forgettable — you can basically replace any of them with someone else and not affect the story in any significant way, as long as their actions are the same. But it’s all about human curiosity and the drive to investigate and understand everything trumping all of the forces that hold us back, like fear of the unknown, or fear of investing resources into pure science with no guarantee of a practical return. Really, the explorers in the story got nothing actually useful out of Rama — they didn’t bring back any new technologies, didn’t gain any really useful scientific knowledge — but the overall feeling from the story was that the trip was worth taking anyway.

K: Didn’t gain any immediate insights or scientific knowledge. I think it’s important to keep in mind that they didn’t expect to make any big breakthroughs while they were there; they weren’t equipped for it or trained. They were just collecting samples and data. And they did collect quite a bit of that. Of course, the book ends with the setup for the sequel, so I don’t know whether or not we get to see there scentific progress based on the fact that scientists now -know- this space drive is possible; that three legged creatures are a viable evolutionary branch; that organic machines are a way to achieve long-term space flight etc. etc.

J: It was surprising to me that the.. I think it was a xenoanthropologist? He just decided in the middle of the exploration that there wasn’t going to be anything of interest and wandered off to do whatever he usually did. Teach grad students or whatever. It wasn’t worth his time to sit and watch the exploration recordings and talk to his colleagues! Dude, just because there doesn’t appear to be any living sentient creatures doesn’t mean there isn’t things to study once it was clear it wasn’t a natural object. But anyway, at least some of the people thought they should be investigating it as a potential threat. And we humans love to investigate potential threats. We’ll commit all sorts of resources to that. Especially if it’s a potential imminent threat, and Rama was moving pretty quick.

B: Or assume that it is a threat, and try to blow it up — the good old 1% doctrine. Anyway, yeah, I guess I wasn’t thinking through all of the potential scientific benefits of the investigation, including the not-to-be-underestimated boost in support for science when people see what it is capable of when it is allowed to advance. That kind of goes along with other things I remember from the essays I read — how, for example, many inventions and technologies people use in their everyday lives came directly from technologies developed by NASA for the space program. The implication in the story was that if humanity had not been as active in space as it had been, there was no way we could have made it to Rama.

K: Or even been able to get a very good look at it from afar.

K: I did find it interesting that he spent a good bit of time during the first portion of the book talking about near-space collisions with asteroids and kind of attempting to justify why they might be looking for objects like Rama. Because scientists do that all the time nowadays, don’t they? It’s always in the news that some comet might have hit Earth but its trajectory will take it past without any issue. Was that started up after this book? Was it started because of this book?

J: I wouldn’t be surprised if Clarke was behind that somehow, if not this book in particular. It’s nice to think we’ll have the capability of blowing stuff up if we need to. Which I don’t think we currently do at the moment. So we’re watching for stuff, but we can’t do anything about it except shout ‘Duck!’.

B: I actually think I may have read something about near-earth objects in one of those essays as well, or I may just be imagining it, but I also wouldn’t surprised at all if Clarke was influential in getting that program going, at least by drawing attention to the need to have it. And of course, if you listen to scientists, they will tell you it is not a question of *if* we will one day have to contend with an actual planet-killing asteroid headed our way, but when. Not that listening to scientists is fashionable these days. But that is one of the reasons stories like this are good to have — because it’s one thing to say, “Science says we should be doing this,” but it’s another to create an interesting narrative that actually gives reasons why.

K: I suspect if you talked to the average person about planet-killing asteroids, they’d have more to say about Bruce Willis or Elijah Woods than Arthur C. Clarke.

K: It’s always interesting to me what sorts of bees authors get in their bonnets. Clarke obviously had several here: objects approaching Earth; a realistic scenario for an alien encounter (ie, one without any actual aliens); the way in which humanity may respond to perceived threats. But he also visited another trope none too dear to my heart. Yes, I’m afraid Rendezvous with Rama saw the return of the Perky Space Boobs. What the hell is the fascination with this idea?

J: It’s mandatory for any science fiction novel that takes place partly in space or low gravity. Though curiously you never see it mentioned on coverage of actual space missions. ‘Bill, please tell us what the astronauts are wearing.’ ‘Who cares? Look how perky those boobs are!’

K: It’s ridiculous! First, I sincerely doubt the ‘lift’ would be all that noticeable, and in practical terms most women wear something to keep them in one spot anyway. Seems to me men are far more likely to have something unrestrained to float around. But that never seems to be mentioned.

B: I’m going to refrain from analyzing this one, except to say that personally, I don’t care if this trope lives or dies.

J: I’ll bring it back to the name Rama then. All the Roman and Greek Gods were used up, so they moved to Indian ones. But that’s a living religion. Unless it’s not in the future of this book? I just can’t see people saying ‘Hey, here’s this weird thing coming. We’re up to J on the rotation. Shall we go for Judas or Jesus?’

K: Well, yes. Who do you think named it Jupiter? It wasn’t the Pope! It was the Romans trying to honor their god. So I don’t find the use of Rama incongruous at all.

J: Well, Jupiter is a big planet, which is hanging around. This is more on the order of an asteroid or comet that wandered by. I just think it’d make more sense to me if it was named after someone more minor. Or if it was Hindus doing the naming.

B: Well, since Christianity only has the one god, you wouldn’t want to go naming it Jehovah unless you want the name to have world-ending implications, so the nearest equivalent would be to pick from the names of angels, which would have seemed appropriate enough. But I honestly can’t say I know enough about Indian religions to judge just how appropriate Rama is as a name. My traditional five minutes of internet research when I do not know something has not brought me any closer to figuring it out, so I’m going to have to defer to people who know more about it.

K: I don’t think we’re given any indication that Indian astronomers were not part of the international body that decided on how to start naming these things. Though the Roman names won out for most of the planets, we still use many of the Arabic names for stars; the Chinese and the Indians had their own traditional names for the planets and stars and other visible objects, many of which were, surprise, the names of gods. I just really don’t find it to be disrespectful or outlandish. Maybe a Hindu person would disagree, but I really cannot make that call.

J: So there is a movie planned, right? I guess I’d be interested in seeing it. Though I hope it’s not as dull as 2001! I think I might have to wait for the DVD though. In case it is very dull. I can do something else while I watch it.

K: It might be more impactful on a big screen. Or 3D IMAX. It seems like the kind of movie that would be improved by increasing the sense of size.

B: It definitely has all of the components needed for a good movie. I’m sure it’d get the Hollywood treatment — lots of CGI, romantic subplots, more perky zero-G boobage — but I’d probably still be willing to give it a chance.

In the late 21st century, humans were contacted by beings from another universe. These beings provided what looked to be the answer to Earth’s energy problems: an endless source of power with only minimal side-effects. A consequence of this development was the near canonization of the man who happened to be there when the contact was made, and many scientists (more worthy, at least in their own minds) resent this. Thus there is much to be gained by someone who can discover and prove that the “electron pump” is not nearly as perfect as it’s been made out to be.

In the late 21st century, humans were contacted by beings from another universe. These beings provided what looked to be the answer to Earth’s energy problems: an endless source of power with only minimal side-effects. A consequence of this development was the near canonization of the man who happened to be there when the contact was made, and many scientists (more worthy, at least in their own minds) resent this. Thus there is much to be gained by someone who can discover and prove that the “electron pump” is not nearly as perfect as it’s been made out to be.

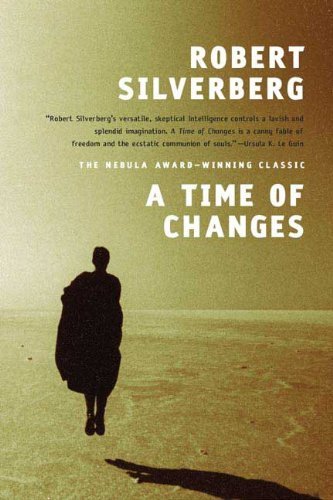

When a man from Earth introduces prince-in-exile Kinnal Darival a telepathic drug from Kinnal’s own planet, he has a revolutionary epiphany. He takes the subversive and obscene step of writing his autobiography — in the first person, as part of a crusade to share this drug and this worldview with others.

When a man from Earth introduces prince-in-exile Kinnal Darival a telepathic drug from Kinnal’s own planet, he has a revolutionary epiphany. He takes the subversive and obscene step of writing his autobiography — in the first person, as part of a crusade to share this drug and this worldview with others.

J: So from 1965 to 1970 is a short decade, but there was a tie in there, so it was actually 7 books. And the first thing I notice about them right off is that they’re all science fiction. Various kinds of sf, but not a single fantasy in there.

J: So from 1965 to 1970 is a short decade, but there was a tie in there, so it was actually 7 books. And the first thing I notice about them right off is that they’re all science fiction. Various kinds of sf, but not a single fantasy in there.