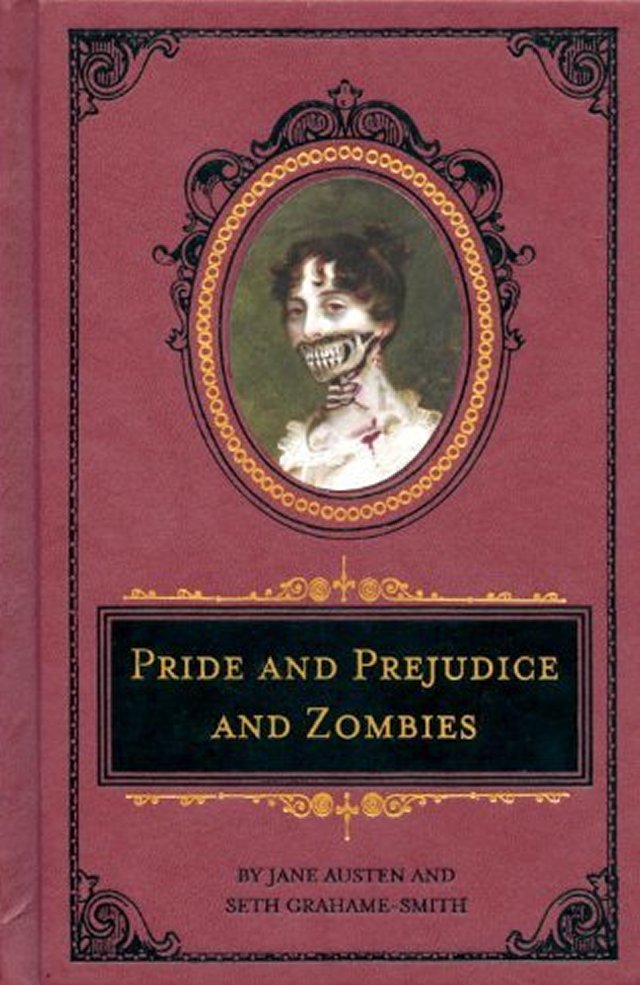

The Plot

The Plot

Fifty-five years ago, the British Empire was faced with an uprising of the non-colonial sort: the dead were walking and they wanted brains. The scourge continues unabated, but life has adapted to cope with the continual threat. The five Bennett sisters have all been trained to fight the menace, but their mother would like to see them well married as well. Enter Mr. Bingley, a single young man of good fortune who has just moved into the neighborhood.

My Thoughts

When this book first came out, I resolved not to read it. The original Pride and Prejudice is my favorite book of all time, coming as close as any book has to my idea of perfection: lots of witty, interesting characters saying pithy things to one another and a happy ending to boot. I love it well enough to hate the vast majority of sequels I’ve tried, because they simply couldn’t live up to the original, or they took liberties to which I objected.

At any rate, my resolve weakened against PPZ. The author had kept a great deal of the original text, and the juxtaposition of zombies with the social machinations of the original might be, as one of Austen’s characters would put it, exceedingly diverting.

The premise is this: about a half-century before our story opens, zombies suddenly began appearing to menace the living. They are witless creatures, not impossible to destroy or even to distract, but doggedly determined in their quest for brains. Zombies seem to have two sources: the already dead may rise again, and the living may be infected by exposure (such as being bitten). In response to this, the army has mobilized, and also the general citizenry has begun to train and arm itself. Even women have received some training, including women of quite high station. The opening of a new economic door to women has seemed to have an effect on society: crudeness and innuendo is more common and there is a great deal more violence.

It’s clear from reading that the author has put at least a little thought into how this situation might change polite society. Unfortunately, in many cases it seems to have been very little. It’s hard to tell whether this is meant to be a “serious” retelling of the story or if it’s just meant to be a silly parody. Different rules apply in the latter case, but just enough effort has been made to maintain the integrity of the plot and story that the argument falls flat — this is not the literary equivalent of Scary Movie. And that makes it all the more galling in the cases where it’s abundantly clear that something has been inserted only because Grahame-Smith just couldn’t resist and not because it made sense in either the original or the re-imagining.

I get the sense, too, that the author didn’t have a great deal of respect for(or understanding of?) some of the original characters. In several places, Austen’s original text is included, but the speaker (or writer) is not the same as the original book – and yet they’re using the exact same phrasing. This is just sheer laziness on the part of the author. The work is almost bookended by the two of the most egregious examples of this: first, where Caroline Bingley takes over some of Darcy’s lines in an early exchange with Elizabeth, and then at the end, where a letter originally sent by Mr. Collins is penned instead by Colonel Fitzwilliam. In neither case are either pair of characters in any way similar and so the reassignment of words is out of character even within the context of this new book.

Similar problems arise when Austen’s text is revised for no apparent purpose beyond dumbing it down for the modern reader, something which happens at multiple points. A single example here will suffice to illustrate the danger of this.

Original:

“No. It would have been strange if they had. But I make no doubt, they often talk of it between themselves. Well, if they can be easy with an estate that is not lawfully their own, so much the better. I should be ashamed of having one that was only entailed on me.”

Zombies:

“No; it would have been strange if they had; but I make no doubt, they often talk of it between themselves. Well, if they can be easy with an estate that is not lawfully their own, so much the better. I should be ashamed of putting an old woman out of her home.”

In the original text, we refer back to Mrs. Bennett’s refusal to admit that the entailment of her husband’s estate makes sense or is legitimate. Further, we have a joke: of course the entailment is pefectly legal, that is the entire problem. In the Zombie version, even though there is no zombie-related information conveyed here, the text is altered: the joke is removed and the reader is not reminded that Mrs. Bennett is ridiculous or of the inheritance situation, but instead is apparently meant to feel bad for her.

There are examples of this sort of careless editing all through the text, toning down the snarkiness of the dialogue and the narrator in some sort of misguided quest to make it more simple. In many cases, these changes cause anachronisms to creep in.

In addition to these changes, there are still more points of fail.

The illustrations: These are just awful. The clothing, which is not particularly mentioned in the text as being different in most cases, is just odd looking. Not at all correct for the time period or even sensible allowing adaptations for fighting and training.

The “Oriental” stuff: I’m not even sure where to begin with all of this. Lady Catherine with ninjas is, I’m sure, the vision that made the insertion of all of this stuff irresistible. And I wouldn’t object to it all overmuch (I leave it to someone else to complain about the potential Racefail aspects of it) were there not such a big deal made about Chinese training versus Japanese training. Because even to my non-expert eyes, it was clear to me that the author was making a distinction he was not prepared to follow through with: Chinese-trained Elizabeth fights with a Japanese sword, there are random bits of Chinese culture at Darcy’s supposedly Japan-inspired home, and so forth. If the author was actually Jane Austen, one might suppose these cross-contaminations were a subtle jibe, but unfortunately, based on the rest of the book, Grahame-Smith is incapable of such a thing.

In Short

This was actually a very clever idea, and I think it could have been very good, with just a bit more effort expended on research and editing. Unfortunately, as it stands, this was definitely a failure, as a parody (not enough liberty was taken) and as a true rewrite (it was too slap-dash and sloppy). I don’t quite regret reading it, but I definitely won’t ever be reading it again, nor will I be picking up the next book, even though it’s to have a different author.