What follows is a spoiler laden discussion of the book The Left Hand of Darkness. Beware if you’re worried about such things. This discussion also veered briefly into the sensitive topics of rape and sexual assault.

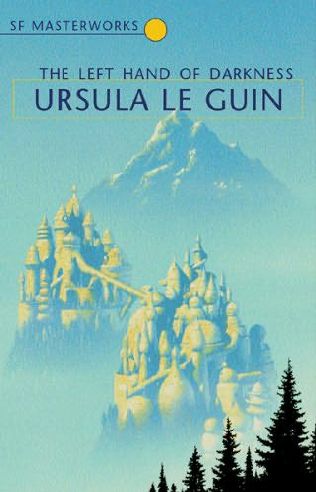

First Mobile Genly Ai is on the planet Gethen, otherwise known as Winter, to convince the inhabitants to join the interplanetary Ekumen, for mutual benefit and exchange of ideas, etc. Coping with the harsh cold environment is the least of his problems, as he seems poorly equipped to deal with the planet’s governments and its people. The fact that they all exist in a non-gendered state most of the time, until they enter kemmer once a month when they can be come male or female, leaves him questioning his own masculinity.

First Mobile Genly Ai is on the planet Gethen, otherwise known as Winter, to convince the inhabitants to join the interplanetary Ekumen, for mutual benefit and exchange of ideas, etc. Coping with the harsh cold environment is the least of his problems, as he seems poorly equipped to deal with the planet’s governments and its people. The fact that they all exist in a non-gendered state most of the time, until they enter kemmer once a month when they can be come male or female, leaves him questioning his own masculinity.

K: So this month we have The Left Hand of Darkness, by our first female winner for best novel, Ursula K. Le Guin. (Is it Le Guin or LeGuin? I’ve seen it written both ways. On my copy it’s pretty consistently with a space.) And once again we have a book about which I knew little more than its title. In fact, for some reason I have a lot of trouble in my head with ‘The Left Hand of Darkness’ and ‘Heart of Darkness’. Perhaps because I’d read neither.

J: I’ve seen it mostly with a space, I think the space is the proper way. Which isn’t how I tend to type it automatically. The trouble I have is between The Left Hand of Darkness and Children of a Lesser God. Which they don’t even share a common word except ‘of’! As for me, this is another book that I’ve actually read before. In this case, at least twice, and for two different classes in college. Though I’d forgotten quite a lot.

K: The book is pretty much the tale of a ‘first contact’ mission by the interstellar alliance known as the Ekumen with a long lost group of humans. There’s some backstory, obviously, which isn’t really touched upon too much here, though I didn’t find it to hinder the understanding of the story.

J: Yea, I’m not sure how much her Hainish books really tie in to each other or rely on each other. I’ve read a few and they don’t seem to really need you to read the others. Of the ones I’ve read, they seem concerned primarily with introducing you, the reader, to a new society and world.

K: Which means that all we can use to judge the Ekumen by is their sole representative who has any sort of role in this book, an Earthling by the name of Genly Ai. Who I was disappointed to discover was a male, since his name said nothing to me. And who I was further disappointed to discover is something of a jackass.

J: And idiot. Don’t forget idiot. But I was surprised he was black. I didn’t remember that.

K: I was lucky the text kept reminding me at intervals, otherwise I would have forgotten. Not necessarily because I was assuming him to be white but because character descriptions just don’t stick in my head very well. I don’t usually picture characters that way in my head, like a movie.

J: Yea, there’s one part where he’s frostbitten and his face is grey and everything and a little bit beyond that I was reminded he was black and went back to reread that bit. Kind of wondering if she’d also forgotten. But I couldn’t find any evidence she had. I don’t even really picture real people in my dreams. I just sort of know they’re them. I think I’d suck as an artist, even if I had the technical skill.

J: How long did you think he was female for? Because I knew he was male going into it, so I didn’t have a surprise there.

K: It’s not so much that I thought he was female but that for the first part of the first chapter, it’s all told in strict first person with no reference to his gender at all. It’s not until one of the other characters calls him ‘Mr. Ai’ that I knew for sure. And I was sad.

J: I get sad when that happens too. It’s a disappointment when it’s not a female main character.

K: Yeah. And here we had not just a male main character, but one who felt to me as pretty misogynistic. He was constantly disparaging the Gethenians by comparing them to women.

J: Yea, I was disappointed in Earth. :P Get out into space and join the wider galactic community and you still haven’t solved your gender issues.

K: I did wonder if it wasn’t meant to be a symptom of sexual panic – he found the Gethenians oddly attractive and so he had to cast them as women or else the gayness ohnoes!

J: Maybe. Which ties in to one of my major disappointments with the book. No sex!!!

K: For a book that was so very much about talking about this weird sexual evolution of the Gethenians, yeah, there was no sex at all on camera. Almost everyone we actually encountered was strangely celibate.

J: Even when Estraven is in kemmer in the tent, it was never clear to me if ‘he’ had gone female or not.

K: No, it wasn’t. And it didn’t make a lot of sense either — they were traveling for 81 days. That’s not one kemmer, that’s like, three.

J: Yea, it was suspicious that it so happened to be like exactly 26 days into the trip. If she had just said, anywhere, that being in dothe or a hard trek across the ice on low supplies might delay it. Which seems perfectly reasonable, but we shouldn’t have to assume..

K: Since he didn’t seem to be in it right before the trip started. I don’t know. The whole kemmer business seemed biologically unlikely to me. I know the story hints that it may have been some sort of abandoned experiment by the ancients, but… I don’t know. It just seems… unlikely.

J: The plausibility or implausibility didn’t bother me.

K: It did me a bit. Because part of the book was about how the Gethenian sexual cycle — the fact that they were essentially asexual for large portions of the time — came to dominate their society and dictate their progress. Because apparently without sexual urges (the drive for men to impress women??) society progresses at a very slow rate and there’s no real ambition or progress.

K: Le Guin equates asexuality with passivity.

J: And no war.

J: Genly and the woman whose notes we get in one chapter aren’t clear on if the slow progress and lack of war are due to their lack of gender or to the environment of the planet. Do you think Le Guin was maybe being hedgy? Not coming right out and laying it all at the feet of gender.

K: I don’t know. I felt the society was pretty uneven: they’ve adapted very well to the cold, even invented super awesome batteries that anyone on Earth now would just kill for. But there’s no sense of industry or advancement, so where did these inventions come from? My experience in our society is that one invention leads pretty soon to another as other people have their ideas sparked by it, and it’s kind of like a snowball rolling down hill as long as there are materials and conditions that allow people to concentrate on inventing. And nothing we’re shown suggests to me that there -aren’t- these conditions, in spite of the difficulty of -travel-, they all seem to be pretty well set otherwise.

J: I think it’s a common theme in stories about all-female societies. Progress is slow or nonexistent and there’s no war. I don’t know what’s up with that! It’s easy to lay war on men, but I don’t believe they have a monopoly on it. Just like they shouldn’t have a monopoly on science, technology, invention, art!

K: No. I think those things might be -different-, but certainly not disappeared. Though I will note that one of the few things Genly can come up with to say about women when asked is that they aren’t usually scientists or inventors! Frankly, society isn’t yet at the point where we can say -what- the potential of women are in those areas, because I don’t think they’ll achieve that potential in the same -way- as males and there just isn’t the right kind of societal support for that yet.

J: Ah, was it him who said that? I knew I’d read it recently, but I’d filled my head with a couple other books and blog posts all around the same subject since I finished reading it. But we already decided Genly was an idiot and a jackass. Why they picked him to be First Mobile, I have no idea. If it were me, I would’ve picked someone intersex or genderqueer. Someone who’d have a chance of not being so gender-biased. And maybe someone who understood politics better. Unless this was all a test of Gethen. ‘Can you handle this guy who’s all caught up in being macho?’

K: It was he who said it. And it made me sad. It made me sad to remember that people were STILL saying the same thing 40 years later (I’m looking at you, Larry Summers) without understanding any better -why- that might be true. Now, as far as Genly’s fitness as First Mobile, I have no idea. Perhaps it was indeed a test of the Gethen. ‘If you don’t murder this dude, maybe you can join us.’

J: *laugh* Yea, sort of.. if you can handle us at our typical (or even sliding towards not-so-great), we’re good to go. But look at what that woman’s report said. “The First Mobile, if one is sent, must be warned that unless he is very self-assured, or senile, his pride will suffer. A man wants his virility regarded, a woman wants her femininity appreciated, however indirect and subtle the indications of regard and appreciation.” And I’m like.. what? Um, no. Not that I don’t think I wouldn’t be surprised and caught off guard if I went to Gethen and was treated not as a woman, but as a person, but I don’t think I’d be bothered by it. My pride would not suffer. Though, really, wouldn’t they treat me like a pregnant woman? And that /would/ bother me!

K: Yeah. It was really that chapter and having a second character say something so idiotic that I knew that my excuses for Genly’s behavior really were just that, excuses, and it probably wasn’t a well-thought out effort on Le Guin’s part to make him that way on purpose to highlight how dumb it all was. Unless she’s trying to say all of human society is blinded by gender and never will manage to get over it. Ever. That’s just depressing.

J: Well, to some extent she probably picked a man with ‘typical’ 60s ideas on purpose. And it was radical only to make him black. That one chapter actually surprised me when it was revealed to be a woman. The whole book up until that point had been male. Even the Gethenians were ‘men’ and ‘he’. So to find it was written by a woman surprised me. I don’t know if it was meant to.

K: I wasn’t sure what to think of it. It seemed a token chapter in an otherwise nearly female-free book. What was its purpose? To show there were female scientists? To shock us with female scientists? To show us something about Ekumen society? Whatever it was I was puzzled.

J: I think.. to give us a female viewpoint of Gethenian society? By.. having her talk about sex. As an excuse for there being none?

K: I don’t know. Maybe. Maybe not. I wonder if there had been sex (which by definition would not have exactly been straight) would the book still have won the Nebula? -Talking- about alternate sexualities and actually -showing- them are definitely not the same thing.

J: I think it would’ve counted as straight. The /relationship/ wouldn’t have been heterosexual, but the sex would’ve been.

K: In any case, it’s a moot point.

J: Well, to mention my other big disappointment with it, was that the male pronouns were continued throughout. It actually surprised me. That Genly would use them, okay. But Estraven? Bah! Estraven’s chapters all read more Earth human than I thought they should’ve.

K: Yes, that was odd. I guess we have to assume the Estraven entries were originally in Karhidish and they had a pronoun which we don’t, and the translation made it ‘he’, but the fact is they kept using Karhidish words like shifgrethor, so there was no reason they couldn’t have just used the proper pronoun.

J: And things like ‘man’ or ‘son’ which could’ve easily been ‘person’ or ‘child’. I know Le Guin has since stated that the one thing she’d change about the book is to use some gender neutral pronouns of some sort. And I wish they’d release a version like that.

K: Yeah, there was really no reason to be using man and son in the non-Genly chapters especially. I’m not usually a big fan of revisions in older books, but this one would actually improve things.

J: Well, an author revision.. where people could still read the old version if they wanted. And this wouldn’t be dumbing it down for the sake of kids, which a lot of them are. My favorite parts of the book are actually the folktales. Which are also male pronouns. Sigh.

K: Ahh yes the folktales. I didn’t dislike them, but their inclusion, and then the abrupt shift to Estraven’s POV in Chapter 6 did make me far more aware of the -structure- of this book than I normally am when reading. So I broke it down hoping to see some sort of pattern, but there wasn’t: Ai, Tale, Ai, Tale, Ai, Estraven, Science Chick, Ai, Tale, Ai, Estraven, Tale, Ai, Estraven, Ai, Estraven, Tale, Ai, Ai, Ai

J: During that long slog across the glacier, I wish there’d been more than one interruption with a folktale. Even if it was Estraven telling it to Genly while they were hanging out in the tent. I suspect the only pattern was ‘I need to tell people about this now, and this the best way to do it’.

K: Maybe so, though I do wish they had been more tied into the text if that was the case. If they really are just random infodumps, they may be creative, but they’re barely disguised.

J: I guess I mostly liked it because I knew the next chapter was likely to be different from the one I was reading. The whole story from Genly’s point of view would’ve been dull.

K: That is definitely true. And incomplete, since there were things going on of which he was not at all aware.

K: Though that comes back again to how unsuitable he seems to have been for the position of First Mobile.

J: Yup. I bet he wasn’t even from Iceland or Canada, which also would’ve made some sense.

K: Hmm. Now I feel like he said where on Earth he was from, but I can’t remember when he said it and skimming through I can’t find it.

J: I don’t remember him saying. Probably something stupid like Hawaii or the Sahara Desert.

J: Shall we talk about things with didn’t disappointment me, but annoyed me quite a lot instead?

J: Minor annoyance – the word ‘bisexual’ to mean a society with two sexes. Is that the right word, even though it sounds wrong? Larger issue.. the Zanies, which are referred to in the same paragraph as ‘insane’, possibly ‘schizophrenic’, and then, bizarrely ‘psychopaths’.

K: Well, I think ‘bisexual’ does mean that, in the same way that ‘bipedal’ means moving about on two feet. But the more common usage has shifted lately to mean being sexually interested in two sexes.

K: Actually I stand corrected. Bisexual used to mean the same as hermaphrodite. So it’s not used correctly.

J: So McCoy was right that tribbles are bisexual?

K: Apparently so!

K: So I’m not sure if there is a single word that describes the fact that humans have two sexes. Binary sexes is the closest that springs to my mind.

K: The issues of insanity and madness was pretty strangely treated. Genly insists that the King of Karhide is ‘mad’, but I didn’t really see why he felt that way.

J: Yea, the king didn’t seem very mad. Oh, you know it bugged me we never got to see him pregnant. He was pregnant, but we never got to see it.

K: In fact, he went into complete seclusion while pregnant. Why? We’re not told if this is normal, if being pregnant is somehow considered unclean or embarrassing, or what. It didn’t make any sense at all except to make him look weak (because he was now a woman?). And then to top everything off, the baby died. Of what cause we don’t know.

J: You would’ve thought, if the kingship was passed down biologically, that there’d be a lot of pressure on him to get pregnant. So why did he wait so late? For one thing, couldn’t he have deliberately put himself around males in kemmer to make sure he was female?

K: It does seem like, even if Karhide wasn’t into the hormones the way the other countries may have been, there were ways to make himself end up female in kemmer. It definitely shouldn’t have been left to chance until he got biologically elderly.

J: Right!

K: So was there anything else that annoyed you?

J: Hrm. Annoyed or puzzled.. back to that chapter written by practically the only woman in the whole book. How is rape impossible?

K: I asked myself that same question. And I came to the same conclusion as you: Uh, what? Because there was no reason given, just this random assertion.

J: I’ll quote. Not that it’ll unconfuse us. “There is no unconsenting sex, no rape. As with most mammals other than man, coitus can be performed only by mutual invitation and consent; otherwise it is not possible. Seduction certainly is possible, but it must have to be awfully well timed.”

K: That still doesn’t even make any sense. I don’t think the very fact of going into estrus is the same thing as invitation and consent; that opens up a whole other can of worms which is, are animals sentient enough -to- consent. I’m not philosophically or biologically or ethically equipped to answer that question. But I do wonder why they are trying to equate the Gethenians to ‘lesser’ mammals.

J: Right. Being.. ready for sex and interested in sex is not.. being willing to have it with a particular person! Plus.. I don’t see any reason someone in kemmer couldn’t rape someone not in kemmer. It does not require a vagina. Which we don’t even know if they have or don’t have when not in kemmer, because we don’t have quite enough detail about that.

K: Yeah. Do they have a smooth area? Are they Ken? But it doesn’t matter, since as you say, rape doesn’t require a vagina. Any kind of orifice will do, and of course sexual assault or molestation doesn’t even require that much.

J: “The genitals engorge or shrink accordingly.” Which says to /me/ that they have something on the outside, but Estraven says something to contradict that later.

J: You’d think forcing someone into kemmer would also be a form of sexual assault. Whether you did it chemically or by putting them in proximity with someone else in kemmer.

K: Yes, I agree. And these are sentient beings — humans — so just because they’re essentially in heat doesn’t mean they /have/ to have sex or want to have sex with /you/. I saw no evidence (and a lot of direct contradiction) that they were overwhelmed by lust with no control over themselves and willing to have sex with whoever was there.

J: Yea. Vulcans they’re not.

J: One last thing I had. Estraven dying seemed abrupt and pointless. I didn’t see it coming. (And since I’ve read this at least three times now, I should’ve!) Just.. dying for the sake of the main character learning something about himself. Or something. :P

K: It did seem kind of useless. Aside from Genly not having to go visit Estre at the end, I’m not completely sure what the use of the death was. Genly’s non-death was what brought about the change in governments; his ship was called before Estraven went on his suicide run; no one other than Genly seemed really to care.

K: Speaking of which, were we ever told why the Gethenians were so against suicide?

J: I don’t think so. Does that sort of thing need a reason?

K: Yes! The taboo against suicide in Catholicism is because you’ve committed a grave sin (murder) without being able to repent of it and confess and be cleansed. So you have no chance of going to heaven. Entirely logical if that’s your belief system. If you don’t have some reason, why would anyone care?

J: Well, I could theorize reasons. Harsh environment and low birth rate means everyone able to work and/or contribute to society is needed. But yea, I don’t think it’s explained.

K: Well, on the flip side, if you kill yourself, they no longer need to provide for you. So you’ve saved them energy and food and resources. So I’m not entirely sure that works — in any case, I just thought it was a weird little thing that got thrown in.

J: I think that about covers everything I wanted to say. I have a book of Joanna Russ reviews and essays and there’s at least two places in that where she talks about this book. So I’m interested in reading those and seeing her take on things.

K: I’m still not sure what I really think of this book. It definitely had a lot of different ideas in it, but on the other hand, I cannot say I enjoyed it or found the story coherent enough to pass my own personal threshold of ‘good’.

J: I liked it less this time than before. Well, maybe. I saw more flaws. But I also saw other things I’m sure I didn’t see before. All the political stuff that was going on and how the two nations were different.

K: Yeah. She did illustrate that pretty well, though in the end it wasn’t clear to me what the government of Karhide actually did for the people.

J: Threw parades for them.

K: Heh. So the next one up is Ringworld, which is another one I confuse with other books. Riverworld and Discworld both sound too similar!

J: It doesn’t just make you think of Ringworm?

K: That too.

The Plot

The Plot

On his 200th birthday, Louis Wu is recruited by an alien to join an expedition to an unknown destination. The reward is the plans for a spaceship drive beyond anything the human race has yet invented. He and the other recruits soon discover their destination is Ringworld, a sort of modified Dyson sphere which consists of a single ring spinning around a sun. Louis, his girltoy, and two aliens soon crash into Ringworld and must try to discover just what it is, who made it, and how they can escape.

On his 200th birthday, Louis Wu is recruited by an alien to join an expedition to an unknown destination. The reward is the plans for a spaceship drive beyond anything the human race has yet invented. He and the other recruits soon discover their destination is Ringworld, a sort of modified Dyson sphere which consists of a single ring spinning around a sun. Louis, his girltoy, and two aliens soon crash into Ringworld and must try to discover just what it is, who made it, and how they can escape. [At least I never slept with Prince Adam.]

[At least I never slept with Prince Adam.]

The Plot

The Plot

The Plot

The Plot

First Mobile Genly Ai is on the planet Gethen, otherwise known as Winter, to convince the inhabitants to join the interplanetary Ekumen, for mutual benefit and exchange of ideas, etc. Coping with the harsh cold environment is the least of his problems, as he seems poorly equipped to deal with the planet’s governments and its people. The fact that they all exist in a non-gendered state most of the time, until they enter kemmer once a month when they can be come male or female, leaves him questioning his own masculinity.

First Mobile Genly Ai is on the planet Gethen, otherwise known as Winter, to convince the inhabitants to join the interplanetary Ekumen, for mutual benefit and exchange of ideas, etc. Coping with the harsh cold environment is the least of his problems, as he seems poorly equipped to deal with the planet’s governments and its people. The fact that they all exist in a non-gendered state most of the time, until they enter kemmer once a month when they can be come male or female, leaves him questioning his own masculinity.