What follows is a spoiler laden discussion of the book Rite of Passage. Beware if you’re worried about such things.

In this 1968 winner, Mia Havero is a 12-year old girl living on ship carved into an asteroid, part of the remnants of the human race who escaped Earth prior to its destruction. In just two years, she faces the Trial, which all children living on the ship must go through. And many don’t live through. We follow her adventures growing up on the ship, losing and making friends, and training to help her survive the Trial. When she and a group of other 14 year olds are dropped off on a colonized planet, they face not only the elements, treacherous terrain, and wild animals, but the unknown colonists as well.

In this 1968 winner, Mia Havero is a 12-year old girl living on ship carved into an asteroid, part of the remnants of the human race who escaped Earth prior to its destruction. In just two years, she faces the Trial, which all children living on the ship must go through. And many don’t live through. We follow her adventures growing up on the ship, losing and making friends, and training to help her survive the Trial. When she and a group of other 14 year olds are dropped off on a colonized planet, they face not only the elements, treacherous terrain, and wild animals, but the unknown colonists as well.

J: So, I was quite surprised to see this book on the list of Nebula award-winning novels! I’d read it in college and kind of thought it was one of those obscure little gems you find that hardly anyone else has heard of.

K: Well, obscure is right, at least from my perspective. But that doesn’t always mean very much when you’re not as familiar with parts of the genre. So I had never read this or even heard of it.

J: I couldn’t even tell you how I found it in the first place. It might’ve been one of those books referenced in old(ish) critical essays I was reading at the time. Or possibly by subject headings. From the, now-primitive, college library computer catalog. I had fun with that!

K: If I had heard of it I probably would have picked it up, solely for the novelty of a teenage girl protaganist.

J: Yea. To be honest, though I remembered I really, really liked it. I didn’t remember much. Just, obviously there was a rite of passage, and it took place in a generation ship. I was really surprised at the YA-ness of it on re-reading.

K: Yes, if this was published now it would instantly be plopped in the YA area, maybe with a head-chopped off girl on the cover, which would pretty much guarantee that at the very least hardly any adult males would read it.

J: And it would be a really hard sell to win the Nebula because of it.

K: Ghettoized as YA for girls.

J: Though I bet it would’ve sold really well, especially in the wake of The Hunger Games. Although then perhaps been compared unfavorably with it.

K: I haven’t read the Hunger Games books, but I know enough about them that they did spring to mind as a comparison point. And I can see why it might not compare favorably with a more recent book. It was very… mmm. It wasn’t _dated_ exactly, but it didn’t have the same feel as modern fiction.

J: Not to get off on a tangent — but you haven’t read The Hunger Games?! But I’ll tell you something I noticed that may have been why it felt dated? She explained. Everything. The details of going out on the surface of the ship. The details of constructing a log cabin. The details of soccer. Everything. Indiscriminately.

K: That’s true. There was no expectation that the audience would be familiar enough with these things to just imagine them without all this additional explanation. Though I have to say, the log cabin scene — he didn’t /quite/ plagiarize Laura Ingalls Wilder, but it was a damn close call.

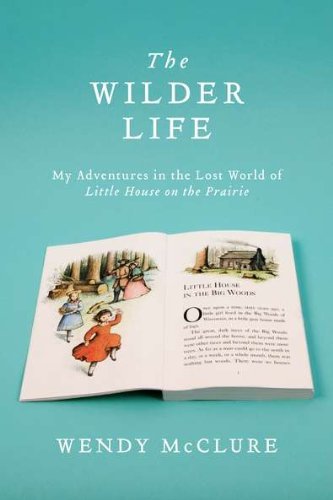

J: I just started reading the Little House books for our other Triple Take reading, so I can definitely see that. On the one hand, it was neat she was treating ‘mundane’ things with equal weight as ‘oooh spacey things’, as you would do if you were living it. They’re all normal to you. But on the other hand, it can get dull and a bit.. ‘why are you telling me this?’ The details of soccer and of log cabin building, to /such/ a degree, were just not necessary.

K: Yeah, it was an odd choice. I can’t say I -minded- especially, but I also didn’t read those sections with as much attention as I probably could have.

J: You know I don’t mind those sorts of details when it’s.. for a purpose. Like if they were actually going to /use/ that cabin. I don’t think you’ve read him, but Steven Gould’s books are really big on planning and doing these sorts of things with lengthy descriptions. Sort of like reading Robinson Crusoe, from what I remember of Robinson Crusoe. If there’s an ulterior plan. ‘I am doing this to survive and improve my life’ sort of thing.

J: Oh, or Clan of the Cave Bear, which we talked about RL earlier.

J: Or even Little House for that matter!

K: Yeah. Exactly. The purpose of the details wasn’t at all clear to me. It didn’t illuminate the society any to tell us the rules of soccer, though it did tell me something that it was called soccer.

J: Oh, odd. I kind of thought he was Russian. Wikipedia says American and that his real name is actually Alexis. Which would’ve been interesting, because I see that as a female name. And his wife’s name is Cory, which I read the opposite way. So maybe he just didn’t think twice about calling it soccer. They do all seem to be speaking English. Though at least he showed a language shift on one colony.

K: Yeah, it is entirely possible that that wasn’t actually a considered choice in any way. Which would be disappointing.

J: Yes. Because he did seem to be trying to be global, at least in some ways. Though the main character.. what’s her name? I am so bad at character names unless they’re particularly memorable… is said to have Spanish and some other ancestry I don’t now remember. Italian? Indian? And her tutor has enough African ancestry to have a South African name.

J: Havero! Have Arrow. Mia was it?

J: See, he gave me a mnemonic and eventually I remembered. Which is actually an interesting parallel with The Hunger Games, which you unaccountably have not read.

K: The names were relatively diverse, yes. More diverse than I would have predicted, given the time period it was written. But like so many authors, even though he gave some thought to a) diversity of names, and b) a rough gender balance among the children, he fell down completely on part c) gender balance among the adult population.

J: Hrrrm. Yes, we see mostly men. And I did notice her survival trainer guy was male. And I was a little puzzled by the gender split when they were building the cabin.

J: They were about 13 when they did the cabin, right? So the boys wouldn’t have been taller than the girls, on average. It would’ve made more sense to me to assign tasks based on individuals. The stronger, the more physically fit, or just whoever showed aptitude after cutting down their first tree.

K: I was having trouble figuring out if the society was supposed to be egalitarian or not. On the argument for, they haven’t turned the women into baby making machines and they seem to have as much autonomy as men to go and do stuff. No one tells Mia she’s out of line for wanting to train for her desired job. Girls and boys appear to endure the exact same trial with no accomodations made for gender.

K: On the argument against, they distributed the cabin work by gender. And we see zero women in positions of authority. Toward the end, they even refer to the ‘men’ on the council. The only adult women we see are flaky (Mia’s mom, that woman who got pregnant) or rigid and annoying (That woman down in the engineering section.)

J: True. Rather like Harry Potter. Only moreso, since we don’t even see female teachers and nurses. Do you think he was concentrating so much on making the kids equal that he just wasn’t thinking whenever he needed to pull in an adult? He defaulted to male and didn’t undefault himself?

K: Probably. You know how annoyed I get though when people start defaulting to male all over the place. It only looks worse when they’ve gone to the trouble to make a female main character. It’s like they’re so busy congratulating themselves for being forward thinking and different that it completely falls apart everywhere else.

J: (I just had a moment of grave disappointment. I thought I had found and bought the sequel to this. But.. there is no sequel? What I have is a collection of short stories. A further disappointment is I thought this supposed sequel might’ve been cowritten with his wife and fixed some of the gender imbalance. Sigh. I’ll just have to imagine my own sequel, I guess.)

K: The collection of short stories contains several stories set in the same universe. And Mia and Jimmy show up very briefly in one. It’s not entirely a sequel.

J: Okay. That lessens the disappointment somewhat. :)

K: Did you read the intro by the way?

J: I did not read the intro.

K: He goes on a bit in there about how he decided deliberately to make the main character a girl. To be different.

J: Well, I can see that! Is that why he won the Nebula? A girl character was so shocking, new, and brilliant? The first since Podkayne of Mars?

K: Ha! You should definitely read the intro before you return the book. As it turns out, after he sold the original story, it was delayed for publication because of Podkayne running in the same magazine. And then he was afraid people would think he’d copied.

J: *snerk!* I thought Podkayne was older. Okay. I will read it.

J: So it was a short story first? Maybe the soccer and log cabin stuff was padding then. :P

K: Yeah. I’m not entirely sure what was the story and where the join came in but I suspect it may have been just the epilogue and a bit of the trial that was the original story.

K: He mentioned about needing to add additional information about ‘why they reacted as they did’ which I assume he means being the vote at the end.

J: Ah. I found it rather odd that they’d assume the next generation would react any differently.

K: Well, it has been typical of our society anyway to become more inclusive and accepting over time. I just was reading an article about it earlier, noting that all those anti gay marriage laws that were passed a few years ago were propelled in for the most part by people aged 50+. Which makes it much more difficult for the younger generation, who more generally favors legalizing same sex marriage, to actually implement it.

K: http://www.slate.com/id/2297897/

J: Yes, but he made a big point of saying how stagnant they are. How their art and their novels are mostly nonexistent and suck when they do exist.

K: Yeah. There were a lot of points being made, some of them contradictory in nature. That the people on the ships, the so called guardians of human knowledge, were so busy trying to preserve themselves and everything that they’d lost their essential humanness which is to change and grow. And a symptom was the complete loss of real creativity. But the colonists didn’t really seem to be doing much better, so it wasn’t like we were supposed to feel for them!

K: What bothered me the most was, I was totally unclear at the end – were just the colonists subjected to the punishment or was it the whole planet? Because they never did bother to find out if those aliens were sentient or not.

J: Yet Jimmy showed creativity when he wrote his ethics paper. So I don’t see what’s so special about art that all other forms of creativity aren’t also suffering. Are they improving their technology or aren’t they? I wasn’t too clear on that.

J: Good question. I don’t think they cared too much about the aliens, just as a ‘slavery is bad’ meme while at the same time not considering them human enough to count for anything.

K: I was pretty puzzled at the whole cultural stagnation thing myself. I can understand the point which was trying to be made, I just find it unlikely that the human imagination could be so very easily stifled as all that.

K: But part of what I think he was trying to say was, if you don’t feel any urgency, you don’t get things done. The people on the Ships lived for a really long time, so long that they didn’t really feel any urgency to accomplish much of anything.

J: You’d think they could’ve realized that and built-in counters to it. Like a rite of passage for 50 year olds. Create something awesome or die!!

K: Oh, but the adults would never have approved of that. It’s only the people who aren’t allowed to vote who can get so easily screwed over.

J: Heh.

K: I wasn’t sure if the whole clothing business was due to a lack of imagination (or maybe a male lapse) on the part of the author, or if it was deliberate, another sign of the Ships deteriorating creativity.

J: What clothing business?

K: When Mia is down on the planet for her trial, she sees some girls wearing dresses and apparently has never seen such things before, because she identifies them as something out of her experience. Which I find very odd, because even if the Ship has a small population, the names indicate it’s a /diverse/ population, or was to begin with. And fashion between cultures is very diverse. I find it hard to believe that no one on the ships ever wears a dress or dress-like item (sari? toga? sarong? kilt?).

K: This is a problem you see often in books, where one culture or group of people is given shorthand by having them always wear the exact same clothing every time they’re encountered. But it just reminds me of a cartoon, like Scooby-Doo, where they’re always drawn the same. It’s not realistic!

J: Ah. Okay. I guess I hadn’t considered it that deeply. I took it as ‘we don’t need to wear clothes because we’re in the perfect environment, but we do because it’s custom, sometimes, or something’. And so they wear what you might typically see an astronaut wearing. Shorts and a tshirt. Which probably makes more sense in zero gravity than other clothes. BUt of course they’re not in zero gravity. And they have wild parts of the ship where more clothes would be nice!

K: Right. That’s what we would wear all the time probably. Because frankly, I don’t enjoy picking out clothes. But I know that a lot of people do enjoy it and find it an expression of their personality. And we even see Mia going ‘shopping’ with her friend Helen, so they do give thought to looking nice and fashionable in their clothing. Which makes me think there must be trends and styles — I’m inclined here to blame Panshin for just not thinking it through all the way.

J: No art means no Teefury and Woot shirts!

K: Tim Gunn weeps.

J: The one thing I did remember about this book that I didn’t remember was _from_ this book (and I suspect a similar idea may appear in Asimov’s work somewhere as well) is Mia’s chosen profession of synthesist. It sounded so perfect. I wanted to be one when I grew up.

K: It was a very interesting profession. And so was ordinologist, which is described around the same time. But what baffled and annoyed me was the bizarre slam against librarians which came out at the same time. Because an ordinologist’s job /is/ library and information science, no two ways about it. Except Mia (and Panshin?) makes a point of saying it’s way beyond the librarian.

J: I can’t find a bio of him that lists any profession other than writer. I thought it’d be interesting if he was a librarian or anything that might shed light on that view of things. But probably he just had the typical picture of librarians. They can find things. But no thought given to /why/ they can find things, because they put them in a findable spot in the first place.

K: I don’t know. I find it hard to believe he could describe the profession so accurately without knowing what he was doing. I’m just not sure why he felt the need to give it another name altogether.

J: Libraries are girly. Ordinology is hard manly science.

J: I have one burning, burning question that I must ask you!

K: Shoot!

J: Why was the tiger purple?

K: It was purple? Good lord, I didn’t even notice.

J: It was totally purple!! Go ahead and look. I’ll wait. :)

K: Yep, it was purple. Reading the description, I get the impression they’re calling it ‘tiger’ but it’s just a word they may be using for any dangerous animal. It doesn’t even seem particularly cat-like.

J: It made me mistrust it was a ‘tiger’ as I knew it. It had a wedge-shaped head or face and that didn’t sound right for a tiger either, but other than that, it didn’t have much description.

K: Yeah. I have no idea what it’s actually meant to be, if anything.

J: And yet, in contrast, the planets seem exactly like Earth. These colonies have not been there long enough to be growing Earth trees all over the freaking place. There is not a thing described as /un/Earthlike, except for the aliens and the gravity.

K: True again. I wonder if this is something that we sort of ran into in some of the other books — the climate and composition of those planets wasn’t actually important to the point Panshin was trying to make, so he just took the easy way out and didn’t devote much time to thinking about them.

J: Ah to be a writer in the 60s, when you didn’t have to think about everything, just your central point. :)

K: Convenient that! But we’re almost out of the 60s now.

J: I was just noticing that myself! 70s, here we come!

The Plot

The Plot

The Plot

The Plot

The Plot

The Plot

The Plot

The Plot